More Buses, Fewer Riders? Thoughts on the Ridership vs Coverage Tradeoff

Transit has to be useful, to be useful

For several years, I worked as a transit planner and scheduler nested in an architecture firm. Along the way, I learned about the concept of a the “starchitect" (“star” + “architect”). Basically, a starchitect is an architect that has established fame inside of (and maybe even outside of) the field of architecture based on the buildings they have designed. A local example here in Chicago is Jeanne Gang. You may not know her, but you probably know her buildings. Jeanne’s firm designed Aqua Tower in downtown Chicago. When it opened, it gained fame as the tallest building designed by a female architect. Aqua Tower lost this title in 2020 when the St. Regis Chicago opened in 2020. Its architect? Also Jeanne Gang!

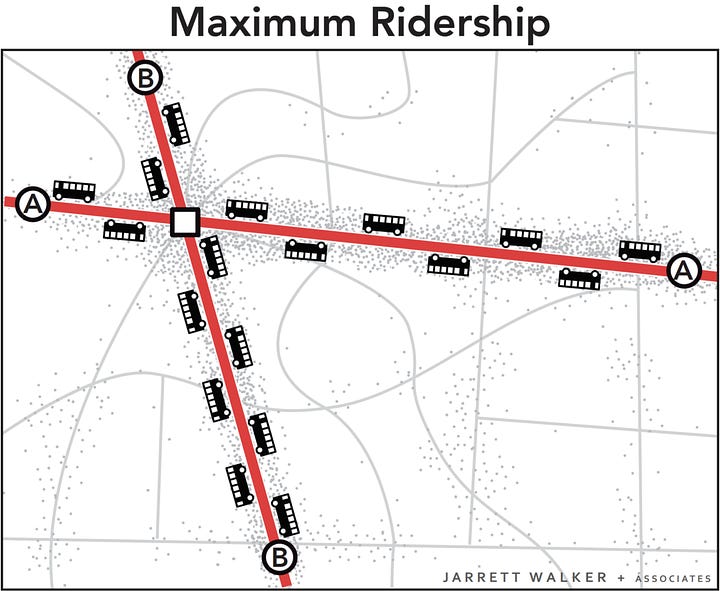

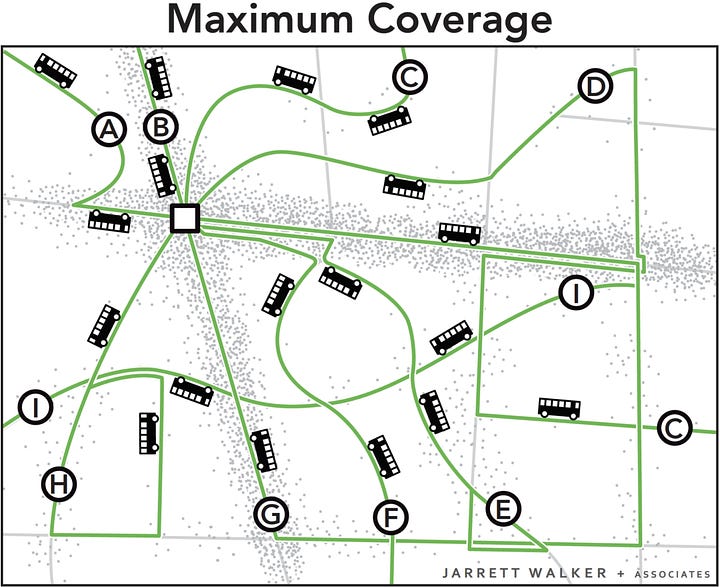

I’m not sure transit has starchitects in that way, but if we do, Jarrett Walker is probably one of them. His book “Human Transit” (released in 2011, updated in 2024) introduced trade-off thinking to the transit industry in a simple, but revolutionary way. Central to his argument is the ridership vs coverage tradeoff (also called the frequency vs coverage tradeoff). When transit authorities are deciding where they will allocate their scarce resources (buses, trains and the people that drive them), they often have competing demands. A focus on ridership means putting these resources where the most people are. A focus on coverage means ensuring everybody has access to some level of transit service. You can hear Jarrett talk about this more in depth over on his blog, also named Human Transit.

I think this simple framing has done wonders for general understanding of what makes useful transit. Before this book, many transit authorities measured their performance on ridership, but allocated their resources for coverage. The ridership vs coverage tradeoff makes transit authorities reconcile this misalignment. Is your transit system’s primary purpose:

A: to move a lot of people around? or

B: to provide some level of mobility to everybody?

The answer to this question, informed by the cocktail of local experience that informs decision making at your transit authority, should guide how you allocate your resources and how you measure your performance. However, in my opinion, if you are operating a fixed route transit network in anything resembling an urbanized area (city, town, suburb, village etc), the answer is A. Your primary focus should be to move the most people around.

Why Should Transit Authorities Prioritize Ridership?

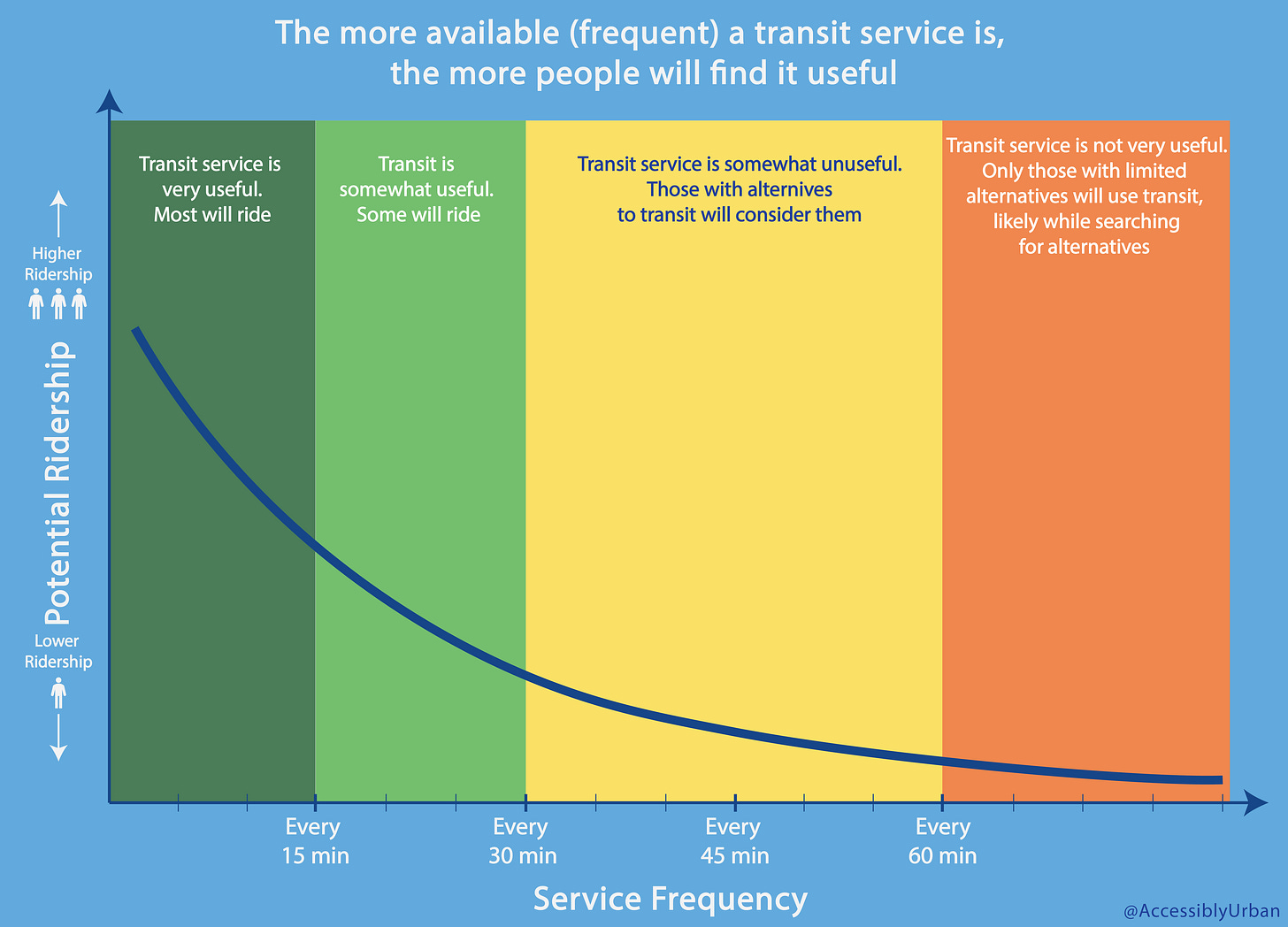

Stating that transit authorities should prioritize ridership over coverage can be a controversial take, but I think it is the best choice for the long-term success. Here’s how I generally view the relationship between transit service frequency, ridership and service usefulness.

Generally, if transit is frequent, it has the potential to be useful to a lot of people. The less frequently it comes, the more it loses that opportunity

A focus on ridership means a focus on frequency, and frequency is what makes transit service useful to the most people. Check out my article “More Buses, More Riders: The Case for Frequent Transit” if you want to know why frequency is key to the usefulness of transit.

Beyond its focus on frequency, I think a focus on ridership helps transit authorities maintain strong internal alignment.

Internal Alignment (n) - Business. Ensuring all departments and employees within an organization are working together towards a common goal

In the private sector, the need to make a profit forces some level of internal alignment (a company that does not make a profit will eventually cease to exist). This is not true for the public sector. In place of a profit motive, public sector services have a collection of values, and promises of social benefit that they are expected to align around. Unfortunately, this leaves a lot of grey area for perverse incentives and individual agendas to creep in. Ridership provides a useful metric for transit authorities to maintain strong internal alignment around.

Can’t Transit Authorities be Internally Aligned Around Coverage?

Internal alignment can be established around any goal, so yes, transit authorities can be internally aligned around a coverage goal. However, I do not think this is wise choice of goal.

A bus, when you look at it with some objectivity, is a silly vehicle. It is not particularly fast or nimble. Its gas mileage is laughable. If it tries to climb too steep of a hill, it will bottom out.

However, a bus does have one thing that it is very good at, and that is carrying a whole lot of people. A standard 40’ transit bus can carry 80+ passengers. A 60’ articulated (bendy) bus can carry 120+ passengers. Space is scarce in cities. Buses (and trains) address this scarcity by moving a lot of people while taking up relatively little space. We’ve been vamping with this concept for a while, and have produced some wacky vehicles along the way.

If you find yourself operating a bus, then you probably have a need to move a lot of people around (If you do not have this need, a bus might not be the best tool). However, in order to move a lot of people around, the bus has to be useful to a lot of people. A focus on coverage ensures you are running a lot of buses, but does little to ensure people want to ride them (5:1 rule).

What About The People That Rely on the Bus?

The primary defense of a focus on coverage is that it ensures those most in need have access to some level of transit service. While I agree that this is a noble goal, I think focusing primarily on this need is detrimental to the delivery of Good Transit. A focus on coverage justifies low quality transit service under the assumption that someone will need to ride it. If someone has limited options to get around, sure they might take the bus that comes every 60 minutes, but will they want to? If they do this time, will they choose it again next time? If they do choose it next time, will they still be there to take it in a year? People have more mobility options now than ever before, and assuming a low quality bus will win in this ecosystem is a fallible approach. A stronger approach for a transit authority concerned with ensuring mobility for those most in need is to focus on ridership, and support land use decisions that ensure those most in need of transit service can locate near it. This means supporting mixed use, higher density development patterns and affordable housing near transit.

As an aside, focusing on ridership does not preclude the provision of coverage service; it simply ensures coverage service is provided in an informed and sustainable way. Cities are marbled places. Maybe an area with increased need can be served via a simple deviation or extension of a ridership focused route instead of with its own route? In scheduling transit, areas of lower productivity can be useful tools for building recovery time into a busy route. Maybe overall demand in an area is low and a demand response (microtransit) zone is the better tool to meet the needs of the community1. Maybe there is high transportation need in an area, but mutual aid is strong and everybody gets everybody where they need to go.

Strike a balance ⚖️

Ultimately, the coverage vs ridership tradeoff is a powerful tool for ensuring transit authorities are internally aligned on how they allocate their resources and how they assess their performance. A transit authority designing for coverage (infrequent routes on several corridors) while assessing themselves based on ridership is destined for headache. While I take a pretty strong, pro-ridership stance here, political realities often mean a balance between ridership and coverage must be struck. Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) provides a strong example of how to strike this balance. The DART Board of Directors approves the ratio of the network that should be dedicated to frequency service vs coverage service (they opted for a 75%-25% balance in 2022). From here, routes are assigned different classifications, held to different standards based on their classifications, and benchmarked against routes of the same classification. This ensures that a route identified as a coverage route is not assessed the same way as a frequent route, while ensuring that a high level of ridership focused coverage is still delivered. Check out their service standards document if you want to get more in the weeds!

Please be careful replacing fixed route service with demand response service. 2-5 passengers per hour is about as productive as demand response service can reasonably be expected to be